While most meteors burn upon entry to earth's atmosphere, some survive the fall all the way to the ground. These are meteorites and many people find these visitors from outer space fascinating; they are highly collectible, and provide scientists with information from outer space.

From Fort Belknap to the Texas Memorial Museum

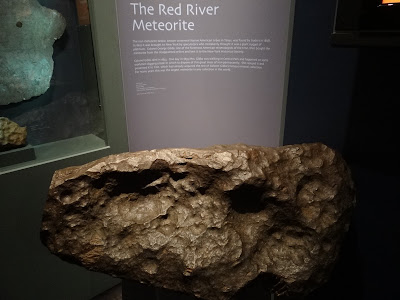

As mentioned, this meteorite can be seen at the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin. Here's the text from the plaque shown in the photo of the meteorite:Wichita Iron Meteorite

Weight 223 pounds

Composition coarse octahedrite iron

This is the fifth largest iron meteorite found in Texas. It has been known to Native Americans since prehistoric times and was first reported in 1813 by John Maley, who was shown the meteorite by the Osage people. This specimen is shown in an 1834 painting by George Catlin which is now in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. In 1856, the specimen was transported 60 miles by the Wichita people to Fort Belknap (now in Young County, Texas). From there it was moved to San Antonio by Major R. S. Neighbors, agent for the Wichitas. It was taken to Austin for exhibit in the Texas Capitol; that structure burned in 1881. The meteorite (160 k.g.) was retrieved from the ashes and stored in the State Archives Building until 1904 when it was exhibited at the St. Louis Exposition. Upon return to Austin it was deposited in the Museum of Economic Geology (145 k.g.) before being transferred to the Bureau of Economic Geology. It was exhibited in 1935 at the Texas Centennial Exhibition in Gregory Gymnasium at the University of Texas, and, since 1938, has been exhibited in Texas Memorial Museum.

Photo of Wichita Iron and plaque taken 1999, Texas Memorial Museum

|

| Texas Capitol which burned in 1881 |

An important document that crops up in conjunction with the history of this meteorite is Catalogue of the meteorites of North America, to January 1, 1909 (henceforth I'll just call it the Catalogue). This document indicates it was transported to San Antonio in 1858 or 1859, then later to the old Texas Capitol building that burned in 1881. In describing the meteorite after the fire in the Capitol building the Catalogue says "There is no appearance of any effect from the Capitol fire through which it passed; very probably the weight of the mass may have carried it rapidly, on the giving way of the floor, down to some position in the basement in which it was sheltered from the heat by masonry accumulated over it." After the fire, the meteorite was moved about, eventually winding up on exhibit at the Texas Memorial Museum, where it has remained since 1938.

The history from Fort Belknap to the Texas Memorial Museum seems pretty clear. But its history before Fort Belknap is where the true lore and mystery of the meteorite lies; and where the history and prehistory is less certain. It's my guess -- and I'm not an expert on meteorites -- that there was some confusion and conflation of stories about the Wichita Iron, and at least one other meteorite of fame, the Texas Iron. (Texas Iron is also known as the Red River and resides in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History)

But first, some of the lore ..

Some of the lore associated with Wichita Iron

The George Catlin painting referenced on the plaque is Catlin's "Comanches Giving Arrows to the Medicine Rock" (dated 1837-1839) and clearly the Comanche among others believed the meteorite held great powers. Of the meteorite Catlin made the comment: "A curious superstition of the Camanchees (sic): going to war, they have no faith in their success, unless they pass a celebrated painted rock, where they appease the spirit of war (who resides there), by riding by it at full gallop, and sacrificing their best arrow by throwing it against the side of the ledge."The Catalogue features some of the same lore about the Wichita Iron: For many years its existence was known to the Comanches, who regarded it with the highest veneration and believed it possessed of extraordinary curative virtues. They gave to it the names Ta-pic-ta-car-re (Standing Rock), Po-i-wisht-car-re (Standing Metal), and Po-a-cat-le-pi-le-care-re (Medicine Rock) and it was the custom of all who passed by to deposit upon it beads, arrowheads, tobacco, and other articles as offerings ... [among the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches the meteorite] had been setup as a kind of 'fetich' (sic) or object of worship or veneration by the Indians, 'who revered it as foreign to the earth and coming from the Great Spirit,' at a point where several converging trails indicated periodical visits to the spot."

A variation on this story (possibly taken from the Catalogue?) was repeated in the Claude News in 1933: "The Comanche Indians, who came into possession of the meteorite, regarded it with awe and veneration .. They gave it the name of Po-a-cat-le-pi-le-car-re, meaning (Medicine Rock) and when passing by it would kneel to deposit upon its surface beads, arrow-heads, tobacco, etc."

Where was the meteorite before Fort Belknap?

There seems to be general agreement that, as indicated on the plaque, in 1856 the meteorite was transported some 60 miles to Fort Belknap, then Neighbors had it transported to San Antonio. But from where was it transported to Fort Belknap?Once the meteorite was in Austin, scientific research was done on the meteorite and published in 1884; the reference is Mallet, J. W. (1884). "On a mass of meteoric iron from Wichita County, Texas". American Journal of Science, (166), 285-288. One geologic website referencing this paper indicates the meteorite was brought to Fort Belknap from near the current town of Electra, TX, in Wichita County ( lat / long 34.0666666667, -98.9166666667). This is close to the Red River, about 60 miles north of Fort Belknap, so this jives with the Memorial Museum plaque and other accounts. Interestingly (and maybe not coincidentally) if you look at this location on a map it's only about 40 miles east of Medicine Mound, TX, a site that was considered sacred to the Comanche.

Was the Wichita Iron moved to Wichita County?

Some lore suggests the Wichita Iron was moved to its location from Wichita County.A friend, anthropologist Linda Pelon, has written about the meteorite, with possible connections to the Santa Anna Mountains in Santa Anna, TX (Click here for Santa Anna Historical Development Organization article). The Santa Anna Mountains are generally thought to be named after the Comanche chief of the same name. Her research recounts oral history of a Comanche ceremonial cavern that once existed there and in which the meteorite -- "the fire rock" -- was kept. Linda writes "About 1805 this cavern caved in burying the fire rock beneath tons and tons of sand. It was unearthed by the Comanche women and plans were immediately made to move it to the [Comanche warrior] training camp on Red River. This task was undertaken by the Antelope Eaters tribe of Comanches. The heavy rock was placed on poles and dragged, at intervals, for two years. In [1856] the meteorite, or "fire rock" was taken to San Antonio by Major Robert S. Neighbors".

If indeed the the meteorite were dragged from Santa Anna Mountains to the location near Electra, TX, it's a distance of about 190 miles by current roads. One reference I saw (but can't put my finger on right now) indicated the "two years" was not just the time to transport the meteorite, but also involved the time spent digging it out of the cave in.

History is so messy ...

So far so good? Well .. but ...Let me begin by reiterating, I am no expert on meteorites, but like any written history, I suspect some of what has been written about Wichita Iron contains inaccuracies, contradictory stories, and possibly some confusion the result of the conflation of stories about another famous meteorite, Texas Iron.

Remember the Alamo?

Let's start with what just seems like a blatant inaccuracy, quite possibly the result of just a simple typo. In the first paragraph of the introduction to the Wichita Iron in the Catalogue (p. 486), it says Maj. R.S. Neighbors obtained the meteorite (brought to Fort Belknap) "during the month of May, 1836". Hold on; remember the Alamo? Everybody was pretty much occupied in Texas that year. No time for meteorites. That date should be 1856. Neighbors was not camped out in Fort Belknap in 1836. A simple mistake, you say? Yep, but once its written down in an "official" book such as the Catalogue .. well, let's just say copy and paste existed back in the day just like it does today and I've seen that date quoted elsewhere (see my postscript below).J.W. Mallet's 1884 study

Remember earlier I mentioned research done and published by J.W. Mallet in 1884 when the Wichita Iron reached Austin ("On a mass of meteoric iron from Wichita County, Texas). That year an article that ran in the Austin Weekly Statesman about the Wichita Iron included a discussion of his research in which he speculated the meteorite was part of a larger meteor shower in 1814 that also produced a larger meteorite weighing 1,635 pounds. That meteorite is known as the Texas Iron, the largest meteorite even found in Texas. The news article says that the larger meteorite (Texas Iron) was discovered in Cherokee County; from this Mallet speculated the Wichita Iron had been "taken as a sacred treasure" from East Texas, then moved to its location on the Red River. (For clarification, the thinking was that Texas Iron and Wichita Iron were bits from the same meteor; where one fell, the other would have been "close by". This is discussed in the Catalogue).So much for the theory of Wichita Iron being dragged from the Santa Anna Mountains? Well, hold on. The Handbook of Texas cites the Texas Iron as having been discovered east of Albany, TX on the border of Shackelford County, i.e. in West Texas, not East Texas. If that location is correct it was only about 60 miles north of the Santa Anna Mountains. But to muddy the waters further, contrary to Mallet's speculation, research published in 1975 (see Buchwald) would indicate the two were not from the same meteor fall.

So who is right? I'm confused. And when you read the Catalogue description of the Texas Iron (which by the way is also called the Red River meteorite) in the context of its relation to the Wichita Iron one gets the sense they were confused too! To put it in perspective, I remind myself that when Catalogue was written, both meteorites were being examined and written about a good while after the they had been moved. In the case of Texas Iron in particular, according to the Handbook of Texas it was on the move as early as about 1810, and not by a group of scientists, but traders making deals with the Indians. So the Catalogue was being written about a meteorite moved half way cross continent, a hundred years previous, by traders back when Texas was still wild and woolly; back in the day before GPS! The exact location of where it fell was probably, quite honestly, a bit of a guess.

John Maley and the Wichita Iron: the Catalogue's story

The plaque on the Wichita Iron at the Memorial Museum says it was "first reported in 1813 by John Maley, who was shown the meteorite by the Osage people." According to the Handbook of Texas, John Maley was associated with the Texas Iron; no mention there he also found the Wichita Iron. From the Handbook of Texas article on the Texas Iron:The first whites to see it [Texas Iron] were Anthony Glass and his party of American traders, on a mustanging expedition that delivered United States flags to Texas Indians in 1808–09. The following year George Schamp, Ezra McCall, and several other traders evaded a Spanish patrol commanded by Capt. José de Goseascochea to acquire it from the Indians in exchange for guns sorely needed against Osage raiders ... In the 1820s Professor Benjamin Silliman of Yale University, who published numerous articles on the Texas Iron in his American Journal of Science and Arts, collected documents on its retrieval, including journals kept by Anthony Glass and John Maley.

So, did Maley see the Wichita Iron, or not? Well, maybe; maybe not.

In the Catalogue's description of the Texas Iron (there called Red River), there is some indication he may have seen the Wichita Iron, although the Catalogue does not make that connection. In 1808 Anthony Glass and his party, of which Maley was a part, first saw the Texas Iron. The journal the Catalogue quotes from then says "They [Pawnee Indians that had told Glass about the Texas Iron] informed him they they knew of two other smaller pieces, the one about 30 and the other 50 miles distant.

After the Texas Iron had been transported to New York City (1810), the Catalogue then says

In February, 1812, John Maley .. went with a few associates up the Red River, with a view to explore the country, trade with Indians, and (if practicable) to bring away the two remaining masses of metal. He saw one or both of the masses; but being unable to make the remuneration for them demanded by the Indians, he continued his tour west.Maley then made a second attempt in 1813 but his party was robbed by Osage Indians of their "merchandise" (which they were carrying for trade for the remaining meteorites) and horses, and were forced to abort the trip. The Catalogue then says "Undoubtedly, therefore, two masses at least of this metal still remain in that region ..". The Catalogue then goes into a lengthy discussion of where those remaining meteorites might still be located if anyone cared to go get them.

So, the scientists involved in writing the Catalogue knew about the Wichita Iron; and that Neighbors had already acquired it in 1856, and it was residing in Austin. The scientists writing the Catalogue also clearly seemed to think that because Maley had failed to acquire the two additional meteorites in proximity to the Texas Iron (Red River) they remained to be found. From that I conclude they didn't think the Wichita Iron was of the "one or both" Maley saw but failed to acquire

But then again, maybe the Catalogue simply failed to connect the dots, i.e. did not recognize that Neighbors had acquired one of the two remaining meteorites. One source I've seen thinks the latter; that the Wichita Iron, acquired by Neighbors, was indeed one of the two smaller pieces the Indians reported to Glass in 1808 (Wilson, p.87).

John Maley and the Wichita Iron: revisionist history?

Looking at the Catalogue's telling of John Maley's two subsequent expeditions in 1812 and 1813, we might conclude he may, or may not, have seen Wichita Iron. Or maybe he saw "one or both" of two other meteorites. More recent research on John Maley as described in Dan Flores' book Journal of an Indian Trader, Anthony Glass and the Texas Trading Frontier, 1790-1810 only seems to shed further doubt.

Flores says of John Maley's journal (p. 96) ".. scholars now regard [it] as semi-fictitious. ... Despite the firsthand posture of the account, Maley's information respecting the meteorite, and almost all other details of trader life in the Southwest, seem actually to have been secondhand, derived from a close grilling of the hunter-traders in Natchitoches during a visit there between 1810 and 1812."

Flores (p. 97) also discusses "purported journal entries from two trading voyages Maley claimed to have made onto the plains in 1812 and 1813," and that "the details of which he possibly obtained by interviewing an actual trader."

Flores concludes (p. 136, n.35) "My own work editing the Maley account for a master's thesis ... has convinced me that Maley's two claimed expeditions onto the plains are fabrications."

Conflating stories of Wichita Iron with Texas Iron

Reading the Catalogue's description of the Wichita Iron, I wondered if there might be some conflation with the story of the Texas Iron. Here's a couple of examples.Discovered by Spanish; too heavy to move

There is a description of the early history of the Wichita Iron ascribed to U.S. Indian Agent Major Neighbors who had the meteorite transported to Fort Belknap, then to San Antonio. The Catalogue says "According to the Indians the mass was first discovered by the Spaniards, who made several ineffectual attempts to remove it on pack mules but were finally compelled to abandon it on account of its great weight."Discovered by the Spaniards? Sounds a bit like the Texas Iron about which the Handbook of Texas says: "The earliest definite mention of the meteorite, in 1772, is by Athanase de Mézières, who wrote of the Tawakoni Indians' excitement over it.". Of Mézières the handbook says he "embarked on an extraordinary career as Spanish agent to the Indians of northern Texas. In 1770 he carried out the first of several expeditions to the Red River, and in the following year he successfully negotiated treaties with the Kichais, Tawakonis, and Taovayas, and by their proxy, with the Tonkawas.

So maybe in addition to discovering the Texas Iron, Mézières also discovered Wichita Iron on one of those expeditions? Maybe. But let's look at what the Catalogue said again: the Spanish, who first discovered it "made several ineffectual attempts to remove it on pack mules but were finally compelled to abandon it on account of its great weight".

Great weight? The Wichita Iron as listed on the Memorial Museum plaque is 223 pounds; the Catalogue's listed weighted was 320 pounds (presumably samples have been taken over the years?). So the Spanish were unable to move the Wichita Iron because it weighed 300 pounds? That doesn't make sense.

Now the Texas Iron, at 1,635 pounds, that I can understand. In 1810 when the Texas Iron was moved, there were two rival parties trying to be the first to acquire it. The group that first got to the Texas Iron discovered they weren't adequately supplied and couldn't get it moved; it was simply too heavy. It was a second party that got to the meteorite that was able to move it; the Catalogue says they "made a truck wagon, to which they harnessed six horses, and set off with their prize towards the Red River."

Standing Rock

Another thing that doesn't seem quite right besides the weight of the Wichita Iron. The Catalogue in describing Wichita Iron says the Comanches "gave to it the names Ta-pic-ta-car-re (Standing Rock), Po-i-wisht-car-re (Standing Metal), and Po-a-cat-le-pi-le-care-re (Medicine Rock)..".If you have ever visited the Wichita Iron, or seen photos, "standing" is not one of the adjectives that springs to mind. It's not that big; it's shape doesn't seem to jive with the notion of a "standing" rock.

|

| Red River (Texas Iron), Peabody Museum. Photo courtesy Jaci Starkey on Flickr |

"Crossing the river Brassos (sic) about fifty miles we approached the place where the metal was; the Indians observing considerable ceremony as they approached we found it resting on its heaviest end and leaning towards one side and under it were some Pipes and Trinkets which had been placed there by some Indians who had been healed by visiting it."

|

| Old photo of Texas Iron (Red River) at the Peabody |

Major R.S. Neighbors

The description for the Wichita Iron in the Catalogue is attributed to Major R.S. Neighbors. He was Indian Agent both for the Republic of Texas, and for the U.S. after Texas' annexation; he was an explorer on the wagon route between San Antonio and El Paso; involved in establishment and management of the both the Brazos Indian Reservation as well as the Comanche Reservation in Texas. He had a number of dealings with the Comanche and was even adopted into the tribe. All to make the point he had ample opportunity to have heard stories about the "Medicine Rock".If indeed there was conflation between the stories of the Wichita Iron and Texas Iron, it could have started with Neighbors, or perhaps whoever recorded these story for Neighbors (Neighbors obviously never told anyone he retrieved the Wichita Iron in 1836 as recorded in the Catalogue).

Of both the Wichita Iron and Texas Iron it is said the Comanche called them Po-a-cat-le-pi-le-car-re; "Medicine Rock". Just like the confusion that can arise when two people have a conversation about "Washington", one thinking the state, one thinking D.C., it's pretty easy to see how stories about the "Medicine Rock" could get confused. Neighbors may well have heard stories about one Medicine Rock, thinking they were talking about another.

|

| George Catlin's Comanche Giving Arrows to the Medicine Rock, 1837–39 |

I remember after having first heard about Catlin's painting, then seeing a print, I was fascinated. But then I went to the Memorial Museum; upon seeing the Wichita Iron for the first time, I'll admit, I was a bit let down. I just had a hard time envisioning the Comanches of Catlin's painting riding their horses around this meteorite, shooting arrows at it? But then again some people say the same thing about the Alamo.

Just speculating.

Postscript

After reading the initial post of my blog, the good folks at the Yale Peabody Museum mailed some additional materials including parts of a publication, Handbook of Iron Meteorites, by a Vagn Fabritius Buchwald from 1975, which states the two meteorites could not be from the same meteor fall. I'll buy that. But what I find most interesting, and more to a central theme of this blog (was there conflation of stories about the two meteorites; and once it's written done becomes the truth), even at the late date of 1975 Buchwald is parroting the same stories from the Catalogue (or an earlier source?) attributed to Neighbors concerning Comanches, conflated or not, including the obvious inaccuracy that in 1836 Neighbors moved the Wichita Iron to San Antonio! OK, it's probably forgivable; there are no doubt many folks not familiar with Texas history and the battle of the Alamo. The real point is once a mistake is written down, it's awfully easy to copy and paste. Or as I've said in another post about Luna's Jacal in Big Bend, at the end of the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the newspaper man upon learning the truth about Liberty Valance's death says "This is the West, sir, When the legend becomes fact, print the legend."Photos

| ||||

Closer shot of Wichita Iron with eye glasses on display case for context of size. It is hard to believe this was the meteorite of which it was said the Spanish made several attempts to move but were "compelled to abandon it on account of its great weight".

Also hard to believe this is the meteorite which the Comanches called the "Standing Rock"

Frontal closeup, 2016

Photo of Red River (Texas Iron), courtesy of Division of Mineralogy and Meteoritics; Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University. Photography by Kimberley Zolvik

Additional photo of Red River (Texas Iron), courtesy of Division of Mineralogy and Meteoritics; Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University

Plaque on end of Red River (Texas Iron) where part has been sawn off. Photo courtesy of Division of Mineralogy and Meteoritics; Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University

Click here for more on the history of the Red River and Colonel George Gibbs.

References, Notes

Claude News (Claude, Tex.), Vol. 44, No. 26, Ed. 1 Friday, March 3, 1933Austin Weekly Statesman. (Austin, Tex.), Vol. 14, No. 8, Ed. 1 Thursday, October 30, 1884

Catalogue of the meteorites of North America, to January 1, 1909

by Farrington, Oliver C. (Oliver Cummings). Texas Iron (Red River) is discussed on p. 366. Wichita Iron is discussed on p. 486. Click here for copy on Internet Archive

Mallet, J. W. (1884). "On a mass of meteoric iron from Wichita County, Texas". American Journal of Science, (166), 285-288.

"Texas Iron", Handbook of Texas Online, accessed December 16, 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/rzt01. Texas Iron resides at the The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale, and to make things even more confusing it is frequently called the "Red River".

John Maley, Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Maley

Steve Wilson, Oklahoma Treasures and Treasure Tales, p.87

Jaci Starkey, photo of Red River meteorite photo at Peabody Museum

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jacistarkey/

George Catlin's "Comanche Giving Arrows to the Medicine Rock", 1837–39, Smithsonian Art Museum, http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/?id=4005

Photo of Texas Capitol from Portal to Texas History

Dan Flores, Journal of an Indian Trader: Anthony Glass and the Texas Trading Frontier, 1790-1810, Texas A&M University Press, 2000

Buchwald, Vagn Fabritius. Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Their History, Distribution, Composition, and Structure, 1975. As to the speculation that Wichita Iron and Texas Iron (Red River) might be from the same meteor fall, Buchwald says "This is .. out of the question since, structurally and chemically, the irons are as different as iron meteorites can be.".

My grandfather (last name Crow) had a farm in Young County just north of Graham Texas and I can remember when I was a kid of about 12 or so (about 1960) I would go all aroung his property collecting iron "nodules" about the size of an egg or smaller. They were all over the place and it kept me busy each time I went to visit my grand parents farm. I accumalated a small pile of them. Could these have been peices of the Texas Iron you speak of?

ReplyDeleteHi Mike, not being a meteorite expert (aside from this article!) I really don't know. I do remember reading an article about another meteorite and folks finding lots of bits of that. But (again not a geologist) hematite concretions are iron based and Native Americans ground them up for pigment for paint. Anyway, thanks for commenting.

ReplyDelete